First, comes the scent---the Angels are present.

Next comes the fall, and I feel a brushing of wings, growing stronger, more intense until my breath seems to fail me.

First, comes the scent---the Angels are present.

Next comes the fall, and I feel a brushing of wings, growing stronger, more intense until my breath seems to fail me.E. is for Epilepsy by Paula Apodaca

I have been epileptic for 65 years now. I have lived in fear, shame and self-doubt. I have learned to push back to make room for a life, with some of the ordinary comforts and joys life can bring. Our lives are gifts. But we are responsible for living them. I promote speaking and writing about E. We can all make a difference so keep reading...

Friday, April 16, 2021

A Scent of Angels: Falling into a Tonic Clonic Seizure

First, comes the scent---the Angels are present.

Next comes the fall, and I feel a brushing of wings, growing stronger, more intense until my breath seems to fail me.

First, comes the scent---the Angels are present.

Next comes the fall, and I feel a brushing of wings, growing stronger, more intense until my breath seems to fail me.Saturday, December 19, 2020

Shine Your Light Into the Darkness and Your Joy Into the Light!

Thursday, June 13, 2019

The Bell

Therapists tell us that one of man's preeminent fears is being buried alive. The term for fear of being buried alive is Taphophobia or Taphephobia may be the reason mining disasters capture and hold our attention, even when they happen far from our shores. A subset of that fear is the notion of being cremated alive. The sense that if one woke, surrounded by flame, enclosed not just in a box, but also in a cabinet, it would lessen one's opportunity for escape.

Therapists tell us that one of man's preeminent fears is being buried alive. The term for fear of being buried alive is Taphophobia or Taphephobia may be the reason mining disasters capture and hold our attention, even when they happen far from our shores. A subset of that fear is the notion of being cremated alive. The sense that if one woke, surrounded by flame, enclosed not just in a box, but also in a cabinet, it would lessen one's opportunity for escape.In the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this fear seemed to reach epic proportions, evidenced by a series of inventions: specialized, safety coffins with an attached bell and pulley system. These systems were designed so that if one awoke after being buried, they could ring the bell and be rescued. Families often hired grave diggers to wait up through the night just in case a bell rang. This practice encouraged the phrases, "saved by the bell", "dead ringer" and "graveyard shift".

When I was small, I frequently endured status epileptics of the convulsive type. At age 35, I went for a blood test and suffered a massive, violent tonic-clonic event and the folks in the Cigna lab thought I had died in the chair from it. All of them left the room and turned out the lights. Only thanks to my husband, who has experience with my epileptic states, was I not carted out by a coroner.

For me, the idea that one might be perceived dead when she was not seemed possible. I read Poe's short story "Berenice" and a few others by Poe. It seemed to confirm my worst fears, until I really began thinking about it. Still, as calm as I have learned to be, I have told my family NOT to cremate me and to definitely "wake" me for at least three days... And, DO NOT enbalm me.

Just keep me chilled and all will be well...

I think that's reasonable!

Saturday, March 9, 2019

Waiting On "The Cure"

So, I am nearly seventy now. Another couple of years and I will reach that mark in my lifetime and after all this time, I have yet to see a proven cure for Epilepsy. Sure, the drugs have improved. Sure, surgical techniques have improved. But...no "cure" has arrived.

I suppose it is something like arriving in the future and there being no flying cars or teleportation devices. Rats!

A cure for E. is something vague, something to be hoped for, but probably not very likely to occur, at least in my lifetime.

Then what do we do with our hopes? Well, just what we are already doing---walking, running and donating for the Cure. Waiting for it to come. We watch days and then years pass. We read everything we can, we give to organizations who say they are working for a cure. We stay good-natured and optimistic, thinking positivity will cosmically speed things along, but still there is nothing for us. But for many, a cure is their dream...

I have an older sister and she is blind. She has the acronymic RLF. Retrolental Fibroplasia (RLF) was caused in the 1950's by too much oxygen administered to premature infants. She does not sit around waiting for a cure, though, many folks have asked her over the years if she would want to be cured of her blindness. She has always answered "no".

Her dream in life has been to be able to drive a car. She has gotten very excited over the prospect of the self-driving car recently and is hoping she will be able to own and use one one day. Personally, I hope her wish is fulfilled...

It seems, to my way of thinking at least, impractical or implausible to find a cure for an overarching condition like this because there are so many kinds and types of E. And if there was a cure, upon whom would this cure be bestowed? Would a new hierarchy of severity and deservedness be created to winnow the Some from the Many?

I guess I sound a little pessimistic and a bit paranoid here, but these are the kinds of things I imagine with talk of a pending "cure".

I get it---I mean all of us would like to wake one morning to the idea that we are solid and no longer prey to seizures, no matter the kind. I wish for that eventuality, too. I am so tired of having epilepsy. It makes me weary down to the nubs of my soul to have to even think about it. I am so tired of having to say to another person that I had a seizure or that I need to lie down, sit down, drink water, close my eyes, etc. because I feel a seizure coming on. And I am equally exhausted of being teased with the idea of a cure, lingering just around the corner.

If one should materialize, I will be glad. Until then, I am finished waiting for the cure to find me. I think it's a reasonable posture to take, don't you?

Saturday, June 2, 2018

Have You Ever...?

I suppose part of my anxiety is linked with the fact that I do have an aura before an event. This means (at least to me) that any little sound, smell or visual oddity is a signal to be careful where I go, what I do and with whom I do it.

And each time the sequence of events repeats, it makes me feel as though the pattern is set. Epilepsy really cannot be avoided. Convulsions can't be evaded. Seizures of all sorts and kinds can't be talked away or reasoned with. There is no amount of willing or determining that can be done by any one of us that can keep it away or make it stop once it has you. And, for me, there is an almost claustrophobic feeling that I cannot outrun or escape it's onset. Of course, this is how it feels when I am only ruminating on it. We all know that when E. does happen to visit, no one really has the time or luxury to contemplate how it feels.

So this is why I say I am epileptic because contrary to the positive thinking of many folks, I do not deny that my epilepsy has me, and that it has since I was 3 years old. I know it has informed and even formed some of my thinking and development as a human being. But, how do you think of it???

Saturday, March 17, 2018

St. Patrick & Epilepsy...

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

The Way Back...

If there is a clue to epilepsy, then it has to be in our collective past. That is what this blog has entertained since I began writing it. Our collective past makes our present and even our futures possible. We have to do more than offer our experiences in daily living to others. We have to offer some kind of historical perspective, a social perspective, concerning epilepsy.

For me, this is a root component to learning to understand and to live with this condition.

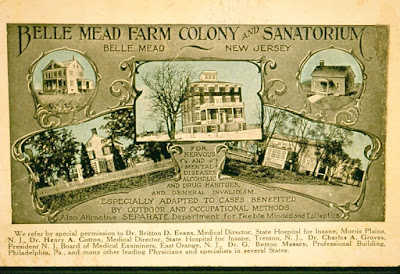

Take for example the photo above. At the turn of the past century, the medical knowledge at the time suggested that persons with epilepsy needed to be hospitalized for the protection of the family and the patient. Care was limited, in our contemporary sense of the word, to labor and fresh air.

Separate accommodations for the "feeble minded and epileptics" often meant various treatments, including segregation, bromides and starvation. It was felt at the time that starving some epileptics resulted in a marked reduction in seizure activity, while bromides created a calming effect.

Hospitalization, then, was complicated. Years later, sterilization for both men and women was considered necessary so that epilepsy could not be passed on in families.

It was under these conditions that doctors became aware of the possibility of death from epilepsy. In close contact with epileptic patients, doctors observed that some of their charges died from the effects of seizing. Today, doctors brush aside the notion that one can die from epilepsy. Yet, it was common knowledge at the end of the 19th century and into the earlier part of the 20th century.

Today, the notion that epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions prompts many doctors to deny the thought that one can die from epilepsy and not to pass the information along to their patients or their families. Sometimes, they simply don't know the range of complications related to epilepsy, sometimes it is a consequence of bad medical school training, sometimes it is a neglected issue because neurologists don't want to alarm families or patients. Whatever the case, the knowledge is frequently withheld.

The experience of living after a family member or friend has died from this condition is terrible. Finding out that doctors knew that this is a possibility and have simply not passed it along is both frustrating and maddening. Activism against this reality has been somewhat effective. Today this possibility is termed SUDEP or sudden unexpected death from epilepsy.

While this is not a posting to make us depressed or grim, it is important to be aware of the possibility and to know that there are folks working to restore this knowledge and import. Doctors must be pressured into telling the whole truth to patients and families. They are not in the position to withhold this kind of relevant information. That is a kind of medical paternalism. It should not and must not be tolerated.

Medical activism should be practiced by those of us who share this condition. We must be proactive with our care. Arming ourselves is the best step we can take to inform and protect ourselves and the people we love.

Part of my effort with my blog is to encourage each of us to stand up for ourselves. Self identification is one of those ways. Confrontation with our healthcare providers is another way.

Learning about our history and then making an application of it can be a useful tool and yet another way of pushing back, for our own benefit and for those not yet diagnosed.

Wednesday, April 8, 2015

Telling Our Own Story...

Further, the notion of illness conveys irregularity, victimization, pity and revulsion (Sontag 1978). In the lives of the chronically ill, the struggle to sustain a balance between the physical and moral aspects of one’s condition can effectively blur the construction of identity, thus impairing socialization and independence by sapping the desire for either. The construction of identity does not take place in a vacuum. In many instances, the identity formation or the construction of Self is a process noticeable to us, as our participation in it progresses.

When, at the same time, errors are made in the telling of the tale, an indescribable blow is made against the owner of the story. A kind of assault is made against the individual to whom the tale belongs. And, when this is done in the presence of a professional, it can undercut the validity of further input, making it seem unreliable.

How we tell the tale is as revealing as the tale itself.

Monday, January 5, 2015

We Are Greater Than The Sum of Our Diagnoses

E. is a heavy label to live with. The culture surrounding it is one of silence and misdirection. It suggests that there is something about us of which we should feel ashamed. The effect of this can be a kind of paralysis: paralysis of speech, of thought, of action.

When I read about other disabled persons, I see a wide variety of writing, social action and speech. Books about the experiences of being disabled are more than just narratives of whether or not to have brain surgery, what drugs to take for my condition or how my doctor’s visit went last month. These others are not content to remain silent and medicalized. They want to live independent lives, think complicated thoughts, write and act in ways that allow them to be greater than the sum of their diagnosis.

When I first learned my diagnosis, I was still a child. I learned the words, the names of the tests, the names of all the drugs I had to take every day. I can recall doing projects in school about E. that included sections of my EEG printouts and answering questions from kids and teachers alike. This was a regular feature of my elementary school life and it continued into high school until an English teacher of mine suggested that since I knew so much about the subject, I should write about it. Confronted with this suggestion, I never said another word in class about E..

I recall working very hard to go to college and got an offer from one in Los Angeles. My mother turned it down flatly. She couldn’t imagine educating me beyond high school: “Spending good money on that sort of thing would be just throwing it away, wouldn’t it?” The worst part of it all was that I accepted this evaluation of myself.

Years later, I made my first attempt at college. I failed. I walked away from it and somehow this seemed to confirm my mother’s original comments. In my mid-40’s I tried again, at the same school. This time I was wildly successful. The experience changed me. I began to analyze the social and cultural structures that come along with a diagnosis of epilepsy. I am finding my voice and writing what we all know: doctors and drug-makers influence information about this condition more than the individuals who experience it.

I think changes are needed in the ways we experience E. We certainly have need of both the doctors and the drug-makers. But we have a greater need of each other. We need to talk to one another about our social experiences and how we worked through the difficulties we encounter. We need to demand a wider variety of articles and books on the subject---something more stimulating and interesting than the standard fare explaining what epilepsy is or the predictable I-triumphed-over-epilepsy tales.

We also need to have a little mercy on ourselves and recognize that we are just learning to speak to each other about our condition. Unlike the deaf, the blind or others who have enjoyed the luxury of being open about their conditions for decades, people with epilepsy have been shut off from each other, their own families and from the larger society until very recently. Speaking up about E. is a good thing to practice now, as we learn to talk about it openly with each other.

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

"Fail First"...What a Really Bad Idea!

The notion that persons with epilepsy should be asked to "fail first" is ludicrous. Since finding a drug or combination of drugs that will control our seizures is, in essence, already a "fail first, then second, then third" proposition. To ask us to give up seizure control just to save a few dollars is a dangerous idea.

Yet, insurers are pushing hard to get lawmakers to invest in the notion that it only makes financial sense. After all, our drugs are really expensive. Some of the older ones are cheaper, but the newer ones are just really costly. I have already taken and tried nearly all of the drugs for anti-seizures that are out there. I am unwilling to go back and begin again. They were crap, gave me terrible side effects, and most importantly did nothing to control my activity.

I have been quite well controlled on the meds I currently take. They do a good job suppressing tonic clonic activity. While they may not work the same for each of us, they work for me! I currently take Carbatrol and Lamictal, brand names only for each. I tried the generics and there was poor control, so I am taking the brand names for each of these and having great success.

Some folks are under the impression that epilepsy, as the 4th most common neurological condition in the nation, is not terribly serious. More of an unpleasant condition, but nothing one could die from. So, if it isn't "life threatening", what could be the harm? Eventually, one would get to the right medication(s), surely. And, while the epileptic is searching through the formulary for a drug that will work, he or she is still having seizures.

I am reminded of a friend, who, on his diagnosis of epilepsy, began the search for a good drug. Unfortunately, he never got the chance to find one. Out shopping at a local mall, he began to feel odd, so he went to the men's room. He was overcome by a seizure, collapsed in the stall and died on the floor, alone.

Yes, we can and do die from epilepsy. Seizures are dangerous. It doesn't take many of them to be lethal. "Fail first" looks to me like "wrongful death". The fools in Washington State, Maryland and other places should hear from us all, with gusto, warning them against the dangers of this foray into financial frugality. Telephone, email, snail mail letters of complaint. Send them this post if you like... They must not do this!

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Invisible Pain and Suffering

Many of us are keenly aware of a kind of barrier that persists, keeping us from excising at least some of the crushing pain and suffering we feel through the act of sharing. While it has long been thought that secret pain is the rule, we have learned that secret pain can twist and warp personalities, leaving some of us more vulnerable to others. In the image below is a good articulation of the landscape the artist imagines of secret pain.

The individual expressed by the central human head, is in agony, the crushing pressure of two screws working to compress his head. Tryng to relieve the pain, He opens his mouth to speak, but finds only a grimace at his disposal. The clock tells us that the individual has endured this condition, and will endure this condition over time. That it will end and begin again, interminably. The artist (who, again, I cannot know..) communicates at the top of the work that there is a barrier at the edge of this territory of pain that cannot be crossed. He even suggests, by the prominent placement of a Death's Head, that the barrier could represent thoughts of death as an escape from pain like this. As you examine the piece, you see other smaller images and note that the shape overall is like a cloud, or a fog of pain.

This image is no fairytale representation. It is edgier, to be sure, But instead of suggesting "silence as etiquette", it suggests fear of pain and suffering and a yearning to end it by any means. That this is the modern etiquette of the already invisible disabled, to suffer silently, then when it becomes too much, yearn to die.

The individual expressed by the central human head, is in agony, the crushing pressure of two screws working to compress his head. Tryng to relieve the pain, He opens his mouth to speak, but finds only a grimace at his disposal. The clock tells us that the individual has endured this condition, and will endure this condition over time. That it will end and begin again, interminably. The artist (who, again, I cannot know..) communicates at the top of the work that there is a barrier at the edge of this territory of pain that cannot be crossed. He even suggests, by the prominent placement of a Death's Head, that the barrier could represent thoughts of death as an escape from pain like this. As you examine the piece, you see other smaller images and note that the shape overall is like a cloud, or a fog of pain.

This image is no fairytale representation. It is edgier, to be sure, But instead of suggesting "silence as etiquette", it suggests fear of pain and suffering and a yearning to end it by any means. That this is the modern etiquette of the already invisible disabled, to suffer silently, then when it becomes too much, yearn to die. David Brooks, in his New York Times op-ed, "Death and Budgets", suggests that one way to cut Medicare costs is to impute to the disabled a sense of a "duty to die", for the good of the nation, rather than to go on existing as a mere "bag of skin" costing millions to sustain. Granted, Brooks was inspired by a friend with ALS whose stated desire is to die before his condition renders him incapable of doing the things he considers significant to living life, and then apparently Brooks coupled this inspiration with the thought that if more folks would think like this, it could be a budgetary windfall for the nation's health care systems. His intention seems to be that we could lighten the load for everyone else if we encouraged the thought that the ill should consider dying more quickly when it is clear that they cannot be cured.

So, referring back to the second image, this becomes a pressure, like the screws represent, on the invisibly disabled. Epileptics have been keen to keep their condition secret for generations. Many of us still will not speak about it, and with pressure like this suggestion that we have a "duty to die when we cannot be cured" the freedom to speak out becomes more difficult.

DO IT ANYWAY!!! SPEAK OUT, STAND UP FOR YOURSELVES...

Rhead, George Wooliscroft & Louis. "Guinevere's Jealousy" from Tennyson, Alfred. Idylls of the King: Vivien, Elaine, Enid, Guinevere. New York: R. H. Russell, 1898.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

A Little Death.

I recall telling him I was not feeling well. I emphasized the statement, saying I was really not feeling well. I had the feeling of hot fingers walking up my back and I thought I was going to be sick.

As it turns out, it was not just a seizure, but two in a row.

Monday, May 2, 2011

The Cage

Friday, April 1, 2011

Testimony to the IOM

Very recently, I was supposed to offer testimony to the IOM. This group is looking into epilepsy and how best we can help persons with epilepsy. So, they have formed a series of meetings and have invited everyone with an oipinion to step forward and offer suggestions.

Very recently, I was supposed to offer testimony to the IOM. This group is looking into epilepsy and how best we can help persons with epilepsy. So, they have formed a series of meetings and have invited everyone with an oipinion to step forward and offer suggestions. There is a terrible gap in the quality of care owing to a lack of comprehension about epilepsy. The phrase “a commonly occurring

neurological disorder” frequently leads laypersons and professionals to

assume that epilepsy is not serious or dangerous to the patient. A more

refined amendment to approaches in medical school education would

benefit patients of all ages, and might make general practitioners and

neurologists more comfortable treating their patients with epilepsy.

Within the past ten years, I have been told by neurologists that “It

could be worse, at least epilepsy can’t kill you” and “Well, we’ll see if you

really have epilepsy: I will take you off all of your medications, and then if

you seize, we will know for certain”. During the same time, GP’s have

suggested that a tonic-clonic seizure has not occurred unless it is

accompanied by urination” and “It is very easy to fake epilepsy. Some of

you people do it for the attention.”

Clearly, these are physicians who are behind on their reading and

who might benefit from a specific educational approach. Initially, I would

suggest a survey into the Attitudes of Physicians toward their Patients

with Epilepsy.

Because physicians can, by their personal attitudes, enhance or

diminish stigma to epilepsy in the community and within the family, they

are also central to quality of life issues. Additionally, physicians with poor

knowledge of epilepsy often have the tendency to view this disorder

according to the germ theory model. They become easily frustrated when

they cannot fulfill their own expectations to find a cure for epilepsy; this

can breed hostility between patient and doctor.

It is also important that health insurers be more broadly introduced

to the neurological sub-specialty, epileptology. The diagnostic codes and

data used to make referral decisions for patients could be smoothed if this

category were supplied to them as a legitimate category in neurology.

So it seems that I am speaking about the need for a more intensified

educational approach, not only for the public at large, but also for the

professional population as a whole.

Treating epilepsy can be as frustrating for doctors as it is for

patients. Still, passing along bad information or resorting to cruelty is not

an answer. A cardiologist would not suggest taking a new heart patient off

his medications to see if he would have a heart attack to confirm a

diagnosis.

Perhaps one of the more ridiculous “cures” ever provided happened

when I was a child. In about 1960, my mother went to see a neurologist.

She talked about me with the doctor, describing my condition in detail. She

mentioned to him that I had long red hair and that she brushed my hair

every morning. She told him that I frequently seized during this process

and more than once, it had triggered status epilepticus. He thought about

what she told him for a moment then concluded that it was my hair that

was the problem. My hair, he told her, was too heavy for my head and

should be cut short to relieve my seizures. She cut my hair off that very afternoon.

So it seems that I am speaking about the need for a more intensified educational approach, not only for the public at large, but also for the professional population as a whole.

We have all learned a lot in the past 55 years of studying and living

with this disorder. I can hardly wait to see how much more we can change

things, together.

Seizing the Moment...

This little bear suggests that we "seize the moment". No doubt, the caption was written by someone without E.,; still, it isn't bad advice. I wanted to say that I have neglected those of you who read my blog in order to focus on an effort to write a collection of short stories on the experience of epilepsy. This has meant that I could no longer siphon off my ideas into my blog postings. It has also required me to take that inward journey to see if there is really anything I can write that is meaningful or significant about experiencing epilepsy.

This little bear suggests that we "seize the moment". No doubt, the caption was written by someone without E.,; still, it isn't bad advice. I wanted to say that I have neglected those of you who read my blog in order to focus on an effort to write a collection of short stories on the experience of epilepsy. This has meant that I could no longer siphon off my ideas into my blog postings. It has also required me to take that inward journey to see if there is really anything I can write that is meaningful or significant about experiencing epilepsy.Saturday, May 1, 2010

Rethinking the Notion of the "Controlled" Epileptic (BADD 2010 entry...)

We hear the term “controlled epileptic” and we think of a person with epilepsy who only needs to take his medicine as he has been told to do to be able to control himself and his seizure activity. Reality for persons with E. is that "compliance" or the taking of one's medication as ordered, often bears no relationship to any specific level of seizure control. In other words, just because I take my meds is no guarantee that I will stop having seizures.

Guilty of both a misunderstanding and a misapplication of the term “controlled”, we are seriously wrong about the epileptic person to whom the term is applied and about the abilities of medical science (e.g. pharmacology) to meet our social expectations.

Most of us make this mistake honestly enough. Our society, like many others around the world, places a premium on moderated behavior. We refer to the act of moderating one's personal behavior as "self control" and identify the strength of character necessary to make such a personal exertion as "willpower". When we think of someone “losing control”, we think of an individual who stubbornly refuses to make use of his willpower to control himself.

We apply this same train of thought to a seizing person with E.. We view his act of seizing as somehow related to his willpower, character or intent and equate it with either disobedience or rebelliousness. Acts of disruptive misbehavior in a public setting, e.g. temper tantrums or seizures, are unacceptable to us and people who put on such displays are “out of control”. Having to witness out of control behavior makes us uncomfortable, distresses us and sometimes angers us.

A few years ago, my husband and I went to visit a friend in the hospital. While sitting in her room, I had a tonic-clonic event, i.e. a convulsion. Nurses were summoned, my husband attended to me, and when he asked them for assistance, they called security. Later, when we were leaving the hospital to go home, the nurse pushing my wheelchair leaned over to me and asked whether "...we had forgotten to take our meds today?".

As insulting as this sounds, it is all too common a response. Persons who should know better by virtue of their professions cannot resist the notion that somehow persons with E. are simply seizing to get attention. The notion of impudent and willful seizing is utterly ridiculous.

Still, there is a desire to believe that the controlled epileptic is a possibility. The idea persists among professionals and non-professionals, as well as among persons with E.. The differance is, persons with E. understand the distinction between the medical application of the term "controlled" and the ordinary use of the word. Too many professionals continue to insist on blaming the patient, rather than admitting that the treatment is insufficient.

The conflict between what is believed to be true and what presents itself as real, looms like a challenge to authority for some people.

But what authority are we speaking of and where did it come from?

In 1951, sociologist Talcott Parsons tried to describe formally what ordinary people already seemed to be acting on at some level. Parsons published his Sick Role Theory, and in it he described two rights and two obligations apparently binding for those who become sick in our society. They are: 1) that the patient is exempt from his normal social duties because he is ill; 2) the sick person is not responsible for his illness; 3) the sick person should try to get well; and finally, 4) the sick person should…cooperate with his physician.

Parsons' theory has been worked and reworked by sociologists to try to take into account the variations not accounted for in the Sick Role Theory. Parsons wrote what many plain folks already upheld: if you are sick, you aren’t to blame and you don’t have to work if you try to get well and obey your doctor, nurse, pharmacist, etc.

Here is the seed of the authority we have been searching for in this piece: an apparent bargain between society tolerating the sick so long as the sick respond by respecting our authority and being obedient.

But, what if they don’t seem to be obeying? What if they seem to be intentionally seizing all over the place?

In 2002, I read a copy of an email exchange between university administrators concerned with how best to handle students with E. who persistently frightened faculty and fellow students by seizing on campus, sometimes during class meetings. Shamefully, the initiator of the exchange was both a Doctor of Pharmacology and of Nursing and should have understood better than anyone the meaning of "control" as related to her students with E..

She queried her colleagues in cyberspace, seeking to know if any of them were experienced with this sort of situation. The replies were varied, but most offered that the best way to handle this sort of disruptive willfulness was to treat it as a problem of student conduct or behavior and not one of disability. They suggested that an "involuntary medical withdrawal" could work constructively in the situation, and in the student’s best interests. The conspirators pointed out that this was a good strategy for skirting the Americans with Disabilities Act, as well.

A few of her respondents mentioned taking such actions at their own universities, regaling one another with their success stories: one student eventually transferred to another university altogether. Problem solved.

What they all seemed to be unaware of was that twelve years earlier, before the email exchange took place, a woman with E., named Barbara Waters, gave testimony before Congress about her own situation at a state college in Massachusetts. She was being harassed and discriminated against by administrators at her college, who wanted to use the tactic of "constructive dismissal" to force her out. She testified she was about to be expelled from school: her college administrators told her that her seizures were "disruptive" and that her presence on campus was "considered a liability" to her school [2 Leg. Hist. (Barbara Waters)].

Thanks to Barbara Waters and others for speaking up. The results have been good for us all because, since 1990, the discriminatory and harassing tactic of “constructive dismissal” is illegal.

The meanings contained within our use of language often include unstated assumptions. Delving into those assumptions requires our participation. To change how people feel about persons with E., we have to be willing to open up and share our knowledge. It is the only way to dispell harmful and simple-minded understandings from either remaining or becoming widely held social expectations.

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Tell Me About Yourself...(my 1st posting, reprinted)

I had two parents. My mother was the most beautiful woman on earth and my father the world'’s most handsome man, and I belonged to them.

Their first child, my older sister, was heroically disabled: the circumstances of her birth were remarkable enough to gain her press coverage for an entire year. Anyone and everyone could see that she was blind and her condition pulled on the heartstrings of them all. I was three when my disability surfaced. No one could tell, unless I was in the violent throes of a convulsion, that anything was amiss. My family overcame their distaste and fear of my epilepsy and cared for me, with the caveat that I would outgrow it one day, if I willed it strongly enough.

A remarkable feature of my life both as a child and as an adult is anger. Not the casual anger that gives expression to the mix of frustration and pain as when one strikes her thumb with a hammer, but a flickering, tentative wisp of emotion that ignites over time and across circumstance toward an explosion, which leads inexorably to oblivion. Owing to the nature of my condition, epilepsy, and the location of its focus in my brain, the anger I sense is often a warning for the onset of seizure activity.

As the sensation grows, I feel an impending doom, a kind of darkening on the spiritual horizon. It can be overwhelmingly intense, stimulating morbid thoughts so that even as a child I knew what it was to contemplate suicide; and I have been long terrified that I would one day relent in the throes of such thoughts. The nearer I come to the explosive event itself, the keener the inconsolable sorrow and sense of desolation become. And then, when the pressure has sufficiently built from within, an explosion of some kind occurs.

Commonly, it is the convulsive action of a tonic-clonic seizure. Sometimes it spends its built-up energy in a less harmful way, as an uncontrollable tremor, a momentary lapse of consciousness or a strong sense of deja vu.

Regardless how the energy spends itself, the end result is the distortion of my life's continuity.

I am certain now that I adapted to living within this distorted reality: I employed tricks of personality and intellect. I learned to read cues in conversation and fill in the empty spaces in the continuum for myself should I lose consciousness briefly; to ask clever questions that would provide me with answers if I didn'’t know how to respond or, to glean from the questioner and his question some nugget that would allow me to make an apparently insightful remark to someone else in the room---in other words, stall, distract, and delight. In so doing, I could only be accused of eccentricity, but never disability.

I transformed myself purposefully, at the age of twelve years, from an introverted child to an extroverted teen so that I could brush away any lingering mark of epilepsy. The urge to transform myself into a perfect being was motivated by a strong sense that I needed to vindicate my mother from the disaster of having two disabled children.

This was born in me one moment when I was about four years old. My sister'’s worth as a human being and my secret understanding of my own worth, as well, was delivered as a casual comment between two women walking opposite my mother, sister and I on a public sidewalk: "“Oh, look how sad...if I were her mother I would have prayed God she had been born dead."

My connection to my mother was primary and endowed with magic. Not fairy-princess magic, but the magic of mythic action: my mother was the one, I believed, brought me back from the terror and oblivion of each convulsion I suffered, and I further believed that without her there to bring me back, I would not return to consciousness. I would remain trapped inside an unconscious blackness until I died.

The two women'’s exchange began slowly to erode my confidence in my mother'’s love and loyalty toward me. If these women from the outside world felt that way, then did she? Did she pray that God would take my sister and I? Did she pray God to take me? Perhaps she did: there was a third child born to my mother and father, also disabled, but she did not live beyond six months of age. She died in our house and everyone said she was better off now and with God. Her death seemed to underscore for me the possibility I was treading on very thin ice as a disabled child.

It had been promised to me that if I willed it strongly enough, I would shed this condition myself. Even my mother, who truly knew better than did the rest that I would never be rid of my condition, suggested that I might try harder to “will away" the onset of convulsions. But, I never seemed to try hard enough and so, in the end, all I could feel about myself was that I had failed. Solace for me was to simply not talk about it any more with anyone, except to mention from time to time that I had once had epilepsy when I was a child.

I was 16 years old when a small town doctor told me I had been cured, because I had no convulsions for over two years. Even when the convulsions returned before I turned 17, like my family, I dismissed them as non-events and clung to the notion I was over the epilepsy for good.

If I could but make the world believe I was perfect and normal, all would be secure and safe. Certainly, the exchange between the women on the street was a powerful one and told me that if I was to feel safe in my own home, among my own family, then I must not be disabled. Since my sister had a value to my mother by virtue of the sympathy she garnered, she would be fine, as long as her existence was an anomalous one. But it was up to me to accommodate and adapt out of my epileptic state. If I had the will, certainly, I could do that.

The truth is, I cannot do it.

I am epileptic. I am not a person with epilepsy, nor am I someone who happens to have epilepsy. My memories are colored by it, just as many of my memories have been obscured by it. I cannot recall a time in my life when my epilepsy was not a part of me: when it did not add to or detract from each experience, decision or act, and it has influenced every step of my development as a human being.

There are still those who feel I am passing as disabled, because I appear whole. They see nothing at all wrong with me. Others believe with an equal conviction that I am malingering, nursing the claim of a disability to achieve some secondary gain from the status. Neither is true, and yet I have experienced this suspicion since I was a small child, whose only society was the family circle.

Even as I aged and moved into conventional society, the features of my childhood experience tagged me: that singular comment from a passing stranger on the street remains with me, as does the distinction between my sister'’s heroic blindness and my ignoble epilepsy. After all, there were no medications that would or could be offered my sister to remedy her blindness, but I had only to take my pills and I might be cured.

A Scent of Angels: Falling into a Tonic Clonic Seizure

First, comes the scent---the Angels are present. Next comes the fall, and I feel a brushing of wings, growing stronger, more intense until ...

-

Some of us take a single AED for our condition. Others of us take more than a single drug. Many of us have been warned about the serious sid...

-

We hear the term “controlled epileptic” and we think of a person with epilepsy who only needs to take his medicine as he has been told to do...

-

To the right is a painting by Evelyn de Morgan from 1916. It is her commentary of Death on the battlefield. Double-click the image to see it...

-

E. is a heavy label to live with. The culture surrounding it is one of silence and misdirection. It suggests that there is something about ...

-

It is not an easy thing to talk about one'’s family. Conflicts abound and committing fact to paper seems to fall short of the true exper...

-

How much can a head of hair weigh? Is it enough to cause your neck from being able to hold your head up straight? I have heard that hair ca...

-

When I went searching for images of pain and suffering online, I was surprised to see that many of those images had to do with tear...