If there is a clue to epilepsy, then it has to be in our collective past. That is what this blog has entertained since I began writing it. Our collective past makes our present and even our futures possible. We have to do more than offer our experiences in daily living to others. We have to offer some kind of historical perspective, a social perspective, concerning epilepsy.

For me, this is a root component to learning to understand and to live with this condition.

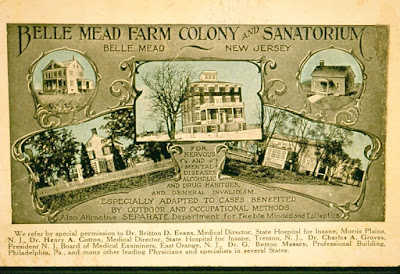

Take for example the photo above. At the turn of the past century, the medical knowledge at the time suggested that persons with epilepsy needed to be hospitalized for the protection of the family and the patient. Care was limited, in our contemporary sense of the word, to labor and fresh air.

Separate accommodations for the "feeble minded and epileptics" often meant various treatments, including segregation, bromides and starvation. It was felt at the time that starving some epileptics resulted in a marked reduction in seizure activity, while bromides created a calming effect.

Hospitalization, then, was complicated. Years later, sterilization for both men and women was considered necessary so that epilepsy could not be passed on in families.

It was under these conditions that doctors became aware of the possibility of death from epilepsy. In close contact with epileptic patients, doctors observed that some of their charges died from the effects of seizing. Today, doctors brush aside the notion that one can die from epilepsy. Yet, it was common knowledge at the end of the 19th century and into the earlier part of the 20th century.

Today, the notion that epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions prompts many doctors to deny the thought that one can die from epilepsy and not to pass the information along to their patients or their families. Sometimes, they simply don't know the range of complications related to epilepsy, sometimes it is a consequence of bad medical school training, sometimes it is a neglected issue because neurologists don't want to alarm families or patients. Whatever the case, the knowledge is frequently withheld.

The experience of living after a family member or friend has died from this condition is terrible. Finding out that doctors knew that this is a possibility and have simply not passed it along is both frustrating and maddening. Activism against this reality has been somewhat effective. Today this possibility is termed SUDEP or sudden unexpected death from epilepsy.

While this is not a posting to make us depressed or grim, it is important to be aware of the possibility and to know that there are folks working to restore this knowledge and import. Doctors must be pressured into telling the whole truth to patients and families. They are not in the position to withhold this kind of relevant information. That is a kind of medical paternalism. It should not and must not be tolerated.

Medical activism should be practiced by those of us who share this condition. We must be proactive with our care. Arming ourselves is the best step we can take to inform and protect ourselves and the people we love.

Part of my effort with my blog is to encourage each of us to stand up for ourselves. Self identification is one of those ways. Confrontation with our healthcare providers is another way.

Learning about our history and then making an application of it can be a useful tool and yet another way of pushing back, for our own benefit and for those not yet diagnosed.

No comments:

Post a Comment